Locusts, Rivers, and Myth – Bonita Ely’s Visionary Art

Bonita Ely’s work blends the abject with the imaginative, highlighting human impact on nature and the resilience of culture.

Bonita Ely reflects on her pioneering art practice, discussing the environmental, feminist, and socio-political themes that define her multi-disciplinary works, from performance to installation, and her evolving approach to ecological activism.

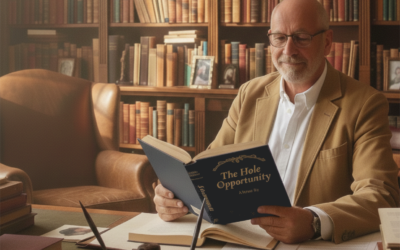

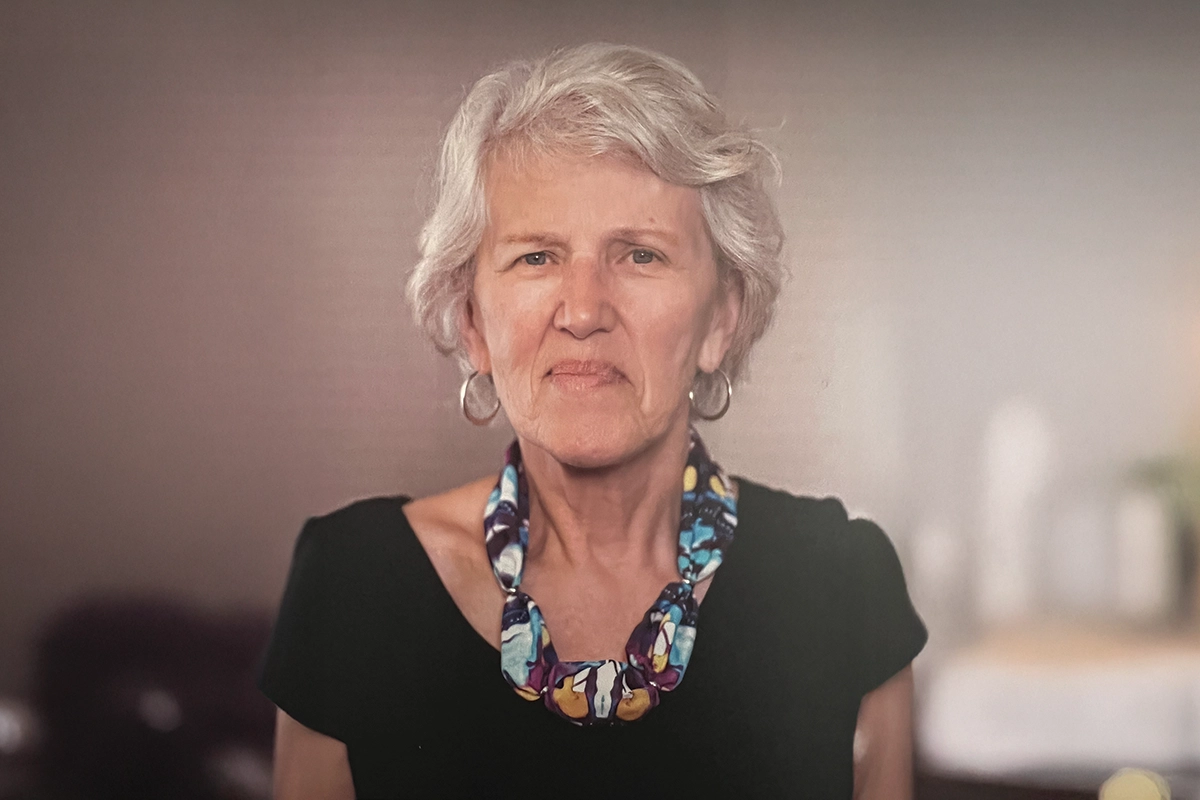

Mosaic Digest is honoured to feature an intimate and thought-provoking interview with Dr. Bonita Ely, an artist whose pioneering work in environmental and socio-political art has resonated deeply across continents and generations. Ely’s artistic journey spans five decades, yet her commitment to addressing critical issues—environmental degradation, cultural heritage, feminism, and the human condition—remains as urgent today as when she first began. Her works, whether immersive installations, performances, or mixed media pieces, invite viewers to engage not just with the art but with the very essence of the issues they explore. Through a mix of wit, forensic research, and a fierce dedication to humanity’s relationship with nature, Ely challenges us to reflect on our impact on the planet, our histories, and our shared future.

Born in post-war rural Australia, Ely’s early experiences on the Murray River shaped her creative and intellectual life. A trailblazer of interdisciplinary art in Australia, her profound fascination with science and sensate communication methods is evident in works such as Murray River Punch, a satirical take on environmental pollution, and the critically acclaimed installation Plastikus Progressus, which tackles plastic pollution through inventive, futuristic narratives. Ely’s capacity to create deeply personal yet universally resonant art has cemented her place as a leader in both Australian and global contemporary art.

Bonita Ely’s visionary art fuses conceptual brilliance with activism, redefining Australia’s environmental, feminist, and socio-political art landscape.

In this exclusive interview, Ely reflects on her expansive career, her early exhibitions like the 1978 Mildura Sculpture Triennial, and the creative personas she’s developed to confront the environmental and societal issues that define our times.

Can you share your experience of exhibiting at the Mildura Sculpture Triennial in 1978 and how it influenced your recognition as an artist in Australia?

I returned to Australia, from New York in 1975 having been overseas for five years. I left Australia straight after finishing Art School – the Australian art scene was so conservative. I was into experimental art.

When I returned, I saw the 1975 Mildura Sculpture Triennial. What a revelation! Earth Works, performance, street art – Fluxus – not the least bit conservative.

I celebrated my homecoming trekking up Mount Feathertop to photograph the panoramic view in all seasons. A modal of the mountain, surrounded by drawings of the changing seasons viewed from the summit were exhibited in the 1978 Mildura Sculpture Triennial.

Your installation, C20th Mythological Beasts: at Home with the Locust People, was developed in New York and involved a deep engagement with environmental themes. How did living in New York shape this work?

In London’s British Museum I’d seen Greek, Roman and Egyptian mythological beasts and wondered what creature combined with the human form would capture our contemporary zeitgeist? Researching the locust’s taxonomy and anatomy in London’s Natural History Museum I decided – locust plagues devour and destroy everything in their path. Perfect.

Air pollution was just as bad if not worse in New York; consumerism was a million times worse. Mark was from a wealthy family so I was able to observe wealthy people’s privileged lifestyles. We lived on the top floor of his father’s commercial building overlooking the Statue of Liberty with polluted sunsets in full view. I photographed the sunsets, later making Sunset Video, its soundtrack composed by my partner, Mark Freedman on Moog synthesizer, evoking the moods and pace of New York City.

Back then viewers could enter the room to watch the video with them.

C20th Mythological Beasts: at Home with the Locust People relax, vegging out in front of TV, watching polluted sunsets for entertainment. The male is a grey puppet; the females are pink dolls. They are surrounded by decorative motifs from nature (we all love nature), oblivious to the pollution they are breathing, living in, contributing to, an indication of our blind destruction of the natural world.

Your performances often explore complex themes like environmental issues and cultural clashes. What inspired you to use invented personas in your work, and how do they enhance the message you aim to convey?

Often my performances require personas inspired by an observation or conceptual devise to set the scene, or to challenge viewers’ preconceptions. For example, seeing Murray River Punch’s demure cooking demonstrator, people thought I would demonstrate a recipe of real food. Groans, gasps and laughter ensued.

Humour draws people in – it’s a serious business interpreting art.

My first performance, Jabiluka UO2 in 1979 addressed the Mirarr people’s land rights, protesting the mining of uranium on their land. I wore a bland, culturally and gender-neutral outfit – the action was the focus, not the performer. The drama of conflicting binaries, the straight line and spiral, plus the pun, UO2 (you owe too), emphasised the conceptual intent.

Demure Virgin Mother Mary has been the traditional iconic mother in Western art. Are real mothers, pregnancy, taboo subjects? Dogwoman is nude, very, very pregnant with a dingo pelt headdress revealing women’s previously unwritten, unknown, ancient history.

In contrast, Controlled Atmosphere’s persona dresses in a neat suit, sensible shoes with Margaret Thatcher’s hairstyle, systematically photocopying copies of photocopies to obliterate the image of pristine Lake Pedder.

These examples demonstrate how an invented persona may be central to enhancing my performances.

The installation Plastikus Progressus at Documenta14 is particularly striking. What motivated you to address plastic pollution in such a creative way, and what response did you hope to elicit from viewers?

Planning the Athen’s iteration of Documenta14, I researched the Kifissos and IIlisos Rivers in Athens, and Sydney’s Cooks River. They were heavily polluted with plastic.

Cooks River is tidal. When the tide comes in a flotilla of plastic parades up stream. At low tide the debris tangles in the mangroves.

Previously (1999) I invented ‘snabbits‘ – genetically engineered rabbits and snails providing food after the Apocalypse. Easy to catch, delicious, what’s not to like? For Documenta the CRISPR method would clean up our plastic pollution. Creatures were genetically combined with Ideonella sakaiensis, a plastic eating bacteria scientists found in a Japanese rubbish tip, creating amphibious, plastic eating creatures to save our planet.

I hoped to motivate viewers to minimise its use and to recycle plastic.

Without water there is no life.

Your recent research on the Great Artesian Basin highlights important environmental issues. How does this research inform your current artistic practice, and what message do you hope to communicate through it?

Water is essential to life, so I suspect it will be a recurrent theme in my art practice.