Chen Wei Ting – Fragmented Dreams and Visual Poetry

Exploring Nomadic Life, Childhood Memories, and Symbolism in Art

Chen Wei Ting weaves poetry and art into reflections on identity and memory, drawing inspiration from childhood symbols, life’s transience, and the sensory impressions of cities he has lived in.

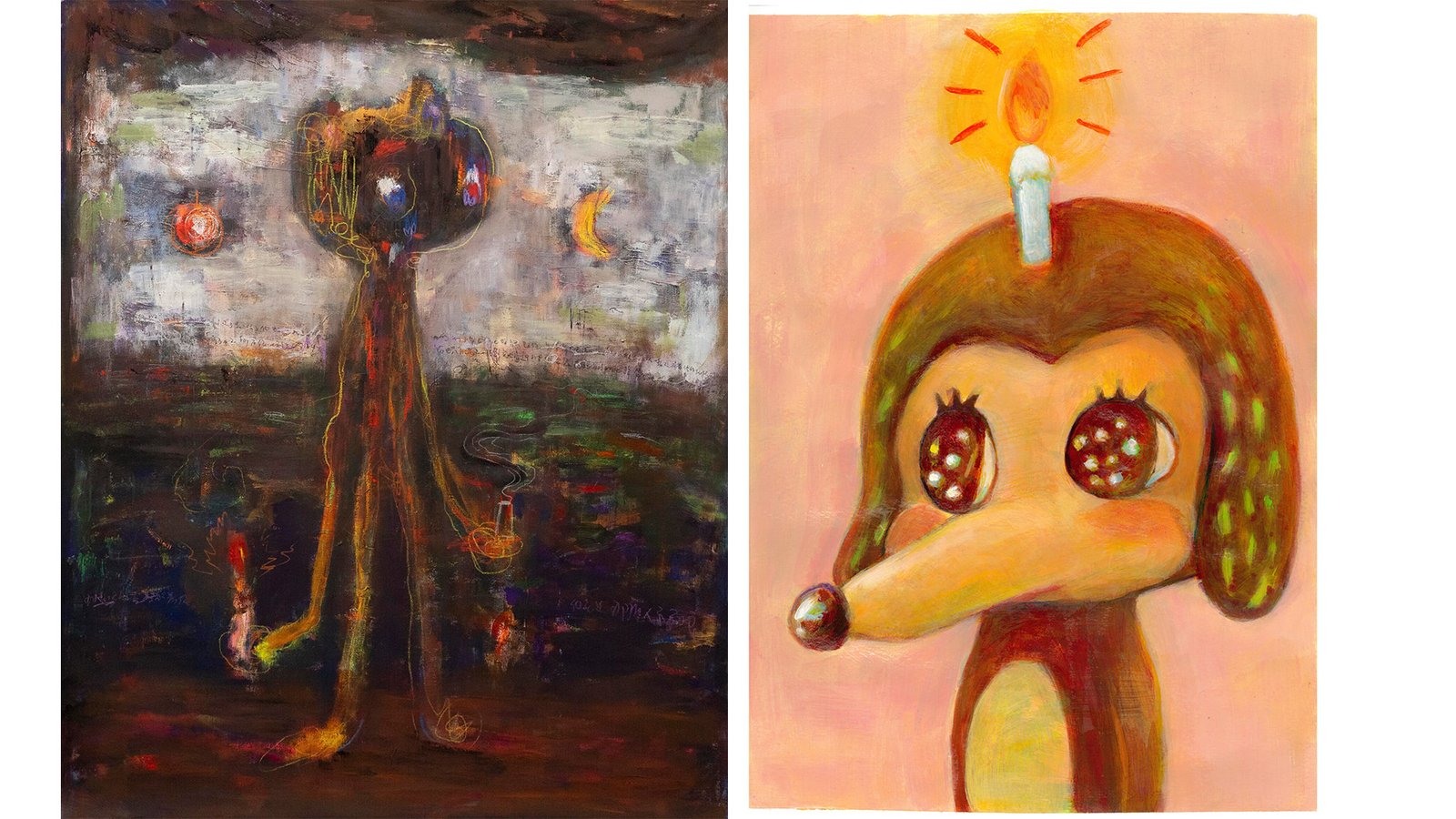

Chen Wei Ting, an artist and poet whose work captures the fragility and beauty of transient moments, masterfully combines visual art with literary expression, creating evocative pieces that speak to the senses and the soul. His art, rich with personal symbols—such as his iconic “Candle Dog” and a tender yellow bear—invites viewers into a poetic world where childhood memories intermingle with existential musings on identity, time, and transformation. Wei Ting’s ability to draw from diverse media and craft a unique visual language of “fragmentation” brings a profound sense of openness and reflection, allowing audiences to explore their interpretations within his dreamlike compositions.

In this Mosaic Digest interview, Wei Ting discusses his journey from Taiwan to Tokyo, where he refined his multidisciplinary approach and found a voice that transcends traditional boundaries. Reflecting on his experiences across multiple cities and cultures, he explores how a nomadic life has heightened his awareness of details in everyday surroundings, from the hues of a sunset to the silence of a fleeting moment. Wei Ting’s words and work invite us to step into the quiet spaces he crafts, immersing ourselves in an aesthetic universe where each image and verse echoes with timeless introspection.

Chen Wei Ting creates mesmerizing visual and poetic worlds, blending personal memories with universal themes of change, innocence, and the search for meaning.

How did your childhood experiences in Tainan, Taiwan, influence your artistic development and the themes present in your work?

Actually, I haven’t spent much time living in Tainan. However, I’ve lived in many places—Pingtung, Kaohsiung, Taipei, Taichung, and currently, Tokyo. I feel like a nomad, but each environment allows me to experience subtle differences. I truly enjoy these experiences, as I immerse myself in every city through various senses—the atmosphere in the air, the distance between people.

These transitions make me particularly attentive to details, such as the color of the sky, animals in motion, and the shapes of roads. Living without a fixed home, I move from place to place like a foreigner, writing my poetry and creating my artwork along the way.

Can you elaborate on the relationship between your poetry and your visual art? How do they inform and enhance each other?

I started writing poetry in high school and later enrolled in the Chinese Literature Department at Fu Jen Catholic University, where I delved into both classical and contemporary literature. During that time, I developed a strong interest in expressing literature through artistic forms, which led me to transfer to the Visual Arts Department at the University of Taipei. After graduation, I pursued further studies at Tokyo University of the Arts, where I explored various creative methods through exchanges with fellow students. From paper-based works to canvas paintings and sculptures, I regard these forms as a kind of “writing” that is closely connected to my poetry.

My literary background has laid the foundation for how I think about visual composition. I interpret my artworks through the lens of poetry, providing viewers with space for interpretation and creating a poetic world filled with “suggestiveness,” “symbolism,” and “openness.” Words, in essence, exist in a virtual space and are closely linked to images. Images serve as carriers that transcend language, like cave paintings, oracle bone scripts, and hieroglyphs, all of which convey meaning through visual forms. As people began to express emotions through writing, literature emerged, with contemporary poetry becoming the most free and intuitive form of expression. However, the expression of poetry is not limited to words.

Artists and poets have long explored how to depict poetic meaning through different forms. Painting, for me, is a visual form of writing, using materials to convey emotions, while poetry expresses emotions through words. It is worth noting that in Japanese, the verbs for “painting” and “writing poetry” share the same pronunciation, emphasizing that both are forms of writing.

What does the concept of “fragmentation” mean to you, and how does it manifest in your artistic process?

Roland Barthes described “fragments” through his literary works, referring to them as the scattered words of everyday life. Barthes wrote about these fragments of life, which, when pieced together, formed a method for interpreting his texts.

For me, personal memories and emotions also resemble fragments—disconnected yet inherently leading back to oneself, like a map where one point connects to another, forming a line that ultimately leads to me. Creating art becomes a process of assembling these fragments into a personal historical narrative, like putting together a puzzle. Each fragment captures a moment in time, whether from the past or present, similar to journal entries. Through these fragments, I aim to gradually complete the vision of my personal utopia.

How do you believe your work reflects the differences between childhood and adulthood, and what insights do you hope viewers gain from this contrast?

The animal figures that frequently appear in my works are inspired by the picture books I read as a child or characters I saw on television. However, growing up is inevitable, and along the way, I gradually came to realize that life presents many complex questions, especially those like “What am I becoming?”

The subjects in my paintings, much like you and me, embody the purity of childhood alongside the loss, longing, and search for identity that come with growing up. In my works, I often use contrasts such as the sun and the moon, joy and sorrow, life and death to tell stories. I believe that these opposing worlds subtly influence each other throughout the process of growth, continuing to coexist and whisper quietly in the background.

Could you discuss your use of childhood memories and symbolic figures in your art? What role do they play in conveying your messages?

The yellow bear that frequently appears in my paintings originates from the character I envisioned during my first oil painting session—it was the image of a bear that came to mind. Perhaps this is rooted in my childhood memories of picture books, where animals often played key roles. Many of the books I read and animated shows I watched as a child featured animals as characters. As a result, I’ve always paid close attention to the expressions of animals, seeing them as emotional beings just like humans.

The dog with a candle on its head, for example, was inspired by a birthday gift I gave to my mother. To me, my mother’s image has always been one of someone who burns herself to illuminate others. These characters, in many ways, carry fragments of my personal experiences, which is why they continue to appear in my work over the years—questioning, mourning, or feeling uneasy. I don’t deny that many of these emotions are not joyful. I firmly believe that humans can truly perceive happiness only because sadness exists; it is through contrast that we come to feel.

What has your experience living and working in Tokyo added to your artistic practice, and how do you see it shaping your future projects?

“Japan is a country filled with symbols.” This statement by Roland Barthes in Empire of Signs perfectly reflects my own impression of Japan. During my first visit, I noticed how mascots were widely used in Japanese advertisements, creating a surreal and whimsical sense of animism. I also became particularly fond of the poetry of Shuntaro Tanikawa, the first Japanese poet I encountered. His works reveal the philosophy embedded in everyday details, much like the famous line from The Little Prince: “What is essential is invisible to the eye; one must feel it with the heart.” Inspired by this, I decided to immerse myself in the finer details of life in Japan.

After arriving in Japan, especially during my studies at Tokyo University of the Arts, my creative process became more open. Collaborating with other artists exposed me to new perspectives, and I began experimenting with a variety of materials, including metal, stone, glass, and wood. A brief drawing workshop I participated in also had a profound impact on me. During that time, we completed many works in a short period, which transformed how I approached the creative process.

The most significant change Japan has brought to my practice is that I’ve started to focus more on observation. In every place I visit, I make it a habit to record thoughts, encounters, and moments, seeking inspiration from subtle traces. This process continuously informs my thinking about the possibilities for future works.