Dan Halter – The Dark Humor of Displacement

Balancing humor and serious commentary, Halter sheds light on the complex realities of Southern Africa

Dan Halter discusses his Zimbabwean roots, migration experiences, and creative process, blending traditional African crafts with conceptual art to explore identity, displacement, and political tensions, all laced with dark humour.

Dan Halter is a dynamic force in contemporary art, known for his thought-provoking explorations of identity, migration, and the socio-political tensions that define his Zimbabwean roots and South African experiences. Born in Zimbabwe to Swiss parents, Halter’s life has been marked by the complexities of displacement, belonging, and cultural intersection. His artistic journey, shaped by these themes, has led him to create a powerful body of work that bridges traditional African craft techniques with cutting-edge conceptual art, producing pieces that are as rich in materiality as they are in narrative depth.

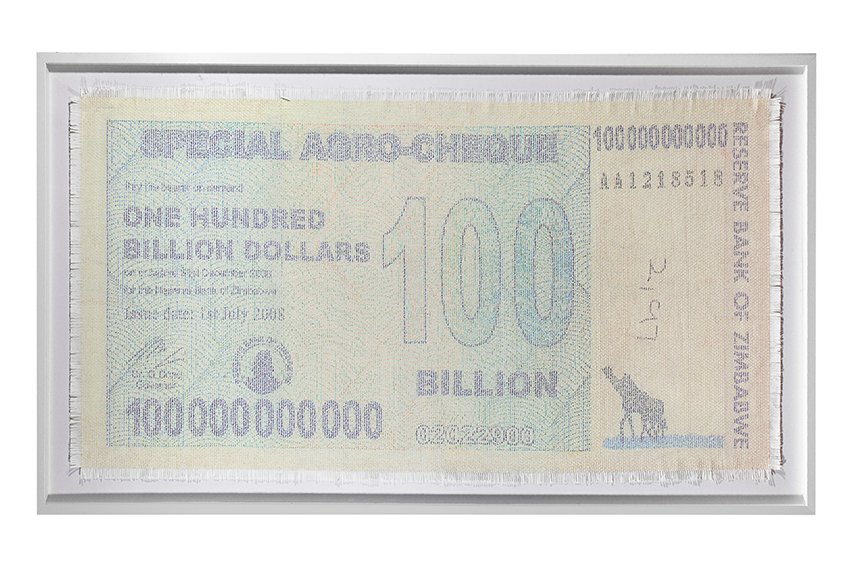

What sets Halter apart is his ability to navigate difficult topics—oppression, migration, and political upheaval—with a masterful blend of dark humour and deep social commentary. His use of everyday materials like woven plastic bags, Zimbabwean currency, and maps speaks to the realities of migration and exile, while also celebrating resilience and resourcefulness. Halter’s works have been featured in prominent solo exhibitions across the globe, from Cape Town to New York, and have resonated with audiences in diverse cultural contexts. His collaborations with local artisans and his commitment to storytelling through material make him a standout voice in the global art scene.

In this interview, we delve into the heart of Halter’s creative process, exploring how his unique experiences shape his art and his evolving perspective on identity, migration, and the role of humour in navigating life’s complexities.

Dan Halter masterfully transforms complex socio-political themes into compelling art, using humor and craft to confront difficult truths.

Your work is deeply rooted in your Zimbabwean identity and experiences as a migrant in South Africa. How do these themes shape your creative process, and how has your perspective on identity evolved through your art?

I was born in Zimbabwe to Swiss parents who felt a strong connection to Switzerland. After high school, I spent a couple of formative years in Switzerland where I attended an art school, but I became homesick and felt like an outsider.

It was then that started to immerse myself in Zimbabwean culture and my interest in Zimbabwean identity was born.

I moved to South Africa to study art at the University of Cape Town. It was around this time that the Zimbabwean government introduced the Fast-Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP), which was followed by a period in which the country began to change. Historical injustices were being addressed and to some extent avenged. Land that had been taken by colonial settlers began to change hands, but his campaign was violent and caused an exodus of white people: ‘white flight’.

The economy there took a significant blow as production in the agricultural sector fell and hyperinflation ensued. Many people began leaving Zimbabwe seeking better opportunities. It was in this context that I started making art about these politics. I spent six months at home in Zimbabwe in 2005 where I made work for my first solo exhibition. Shortly after I left my parents were attacked in their home in Harare. They left Zimbabwe soon after. I think that without this opportunity to make art at home, I would probably not be an artist today. Now I identify as a ‘Swimbabwean’ based in South Africa.

You frequently collaborate with artists like Bienco Ikete, utilizing everyday materials and craft techniques. Can you discuss how these collaborations influence your work and what role materiality plays in conveying your artistic message?

The art and craft scene is very vibrant in southern Africa and I wanted to tap into these skills and methods of production. My idea was to make conceptual art in typical African modes of production.

In Zimbabwe, one can find woven grass baskets inscribed with phrases and these inspired me to start weaving. The increasingly worthless Zimbabwean currency seemed an obvious choice for me to use as a material as it was appropriate to my practice both physically and conceptually. Zimbabwean Maps also resonated with me. During the FTLRP the book Animal Farm by George Orwell was printed serially in one of the last independent newspapers there before they were bombed. This text among others provided material for me to work with.

I met Bienco Ikete, a refugee from the Congo in Cape Town. He was looking for work, and I introduced him to the process of weaving paper. This worked well, and together we developed this concept further. I have also worked with seamstress Sibongile Tete, stone-sculptor Faro Mutize, and wire-artist Kuda Kuimba, amongst others to realise different artworks. The cheap Chinese-made plastic-weave bags commonly used by migrants worldwide turned into another viable material symbolising migration.

The use of dark humour is a recurring element in your art, particularly when addressing complex social and political realities in Southern Africa. How do you balance humour with serious commentary on issues like migration and oppression?

Dark humour seems to be a common coping mechanism in this part of the world. Making light of difficult situations in clever linguistic ways is something I find inspiring. Laughing in the face of dire circumstances can be a delicate equilibrium and it is something that I struggle with. When the balance works it can be effective in communicating a hard truth, like a spoonful of sugar helping the medicine go down.

You engage with both traditional craft and contemporary technology in your practice. How do you see these two seemingly contrasting approaches coexisting in your work, and what narrative does this fusion create?

In Latin, the verb ‘texere’ means both to weave and to write. It gave us the words text and textile. Weaving is writing and writing is a form of weaving.

Weaving was also the harbinger of the computer by virtue of the automated loom invented by JM Jacquard.

In the process of weaving two identical digital prints together by hand, there is a reinterpretation that occurs. I love this fusion between analogue and digital, marrying high-tech and low-tech. To quote Jorge Luis Borges: The original is unfaithful to the translation.

Your exhibitions have spanned globally, from Cape Town to New York and Havana. How does showing your work in international contexts impact the way your message is received, and how do you adapt your narrative for different audiences?

I hope that my narrative communicates something about my experience and way of seeing things. I do not tailor my message for different audiences, although I have made some site-specific works, but my vision and voice is consistent. My work often needs some accompanying text to give some context and make it more accessible to viewers unfamiliar with my practice. In researching my art ideas, I am constantly educating myself and I hope that this can also inform the viewer.

Having participated in numerous artist residencies around the world, how have these experiences influenced your artistic practice and expanded your view on the themes of displacement and global identity?

I am extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to travel for work, as this has broadened my horizons and introduced me to new perspectives. It is interesting to draw parallels between different cultures. The world is both bigger and smaller in different ways to what I previously thought. Human concerns are similar everywhere and so is the way that power manifests itself. It has given me a better sense of my place in the world, of how the world impacts me, and of how I might impact the world.