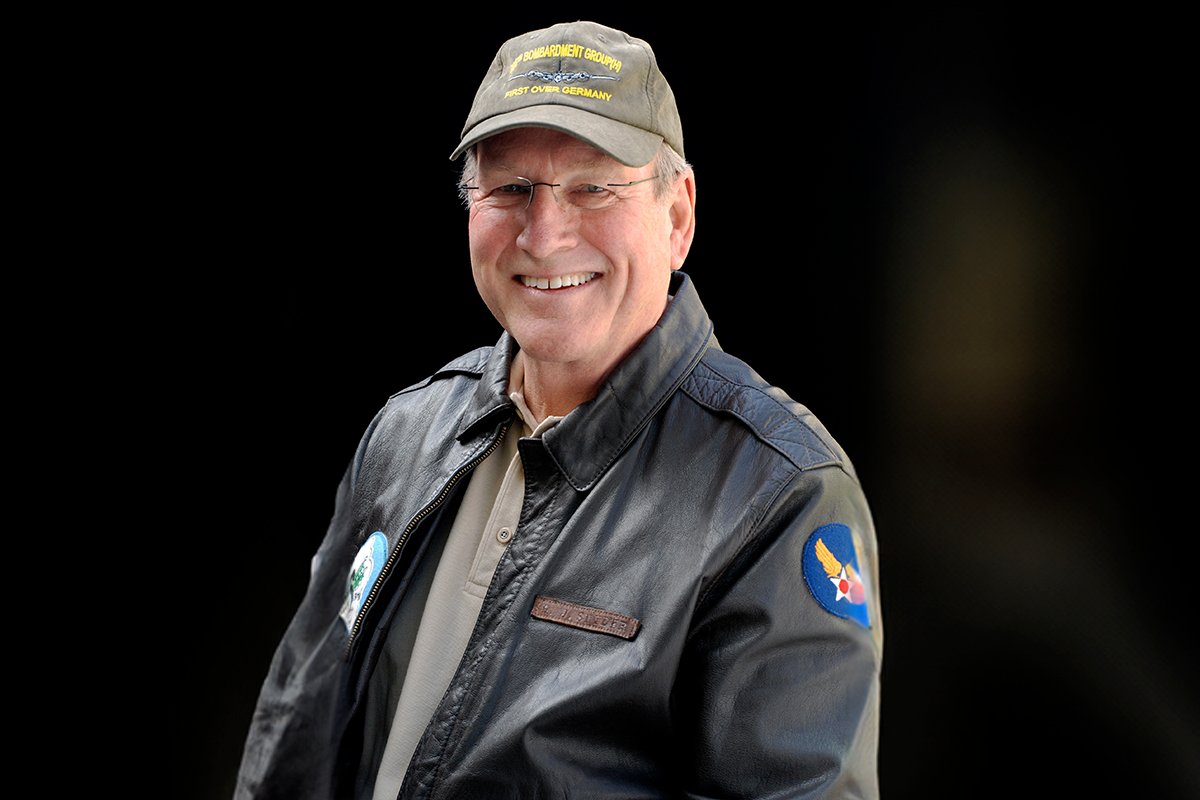

Echoes of Steel – An Artistic Exploration with John Gibbons

Understanding John Gibbons’s innovative techniques and philosophies behind his captivating works

John Gibbons reflects on his artistic journey, the transformative power of light in sculpture, and offers advice for aspiring sculptors.

John Gibbons is a name that resonates deeply within the world of contemporary sculpture. Born in Ireland, Gibbons has built a remarkable career characterized by an innovative approach to steel, which he describes as a modern, flexible, and reflective medium. His education at prestigious institutions like Limerick School of Art and St. Martin’s School of Art provided him with a solid foundation in artistic discipline and creative freedom, shaping his unique vision. Over the decades, he has garnered numerous accolades, including the esteemed Macaulay Fellowship and the Lorne Award, which speak to his exceptional talent and commitment to his craft. Gibbons’ work has been showcased in prominent galleries such as the Serpentine Gallery and is housed in major collections, including the Tate, affirming his status as a leading figure in the field.

Gibbons shares insights from his illustrious career, offering a glimpse into his artistic journey and the philosophies that drive his work. His reflections on the role of light in sculpture, the influence of educational environments, and the importance of international exhibitions reveal the depth of his experience and the thoughtful nature of his practice. Aspiring sculptors will find his advice particularly inspiring, as he encourages them to trust their instincts while navigating the complexities of their own artistic paths.

John Gibbons is a visionary sculptor whose innovative work with steel captivates and inspires, revealing profound connections between art, light, and the human experience.

Your sculptural work, particularly in steel, has a very distinctive abstract quality. What drew you to steel as a medium, and how has your approach to this material evolved throughout your career?

I found steel to be a very modern material with great flexibility and reference. It is also very forgiving. I now work mainly with Stainless Steel as I like the way it engages with light. Painting generates light where as sculpture reflects it – this light I believe is encoded and when focused touches our inner being, our souls, not unlike a QR code we now use almost every day as we travel and shop.

You’ve had a remarkable educational journey from Limerick to London, studying at some of the most prestigious art schools. How did your time at institutions like St Martin’s School of Art shape your artistic vision and practice?

St. Martins saved my life. It was an extraordinary sculpture department with two courses running side by side, each with their own leader and team, A and B, with a wide range of artists as tutors. The A course was conceptual and the B course was made up of object makers. Being as radical as it was, neither course complied fully with these descriptions which in turn gave a great deal of creative freedom to us students. We were expected to produce work for monthly crit’s which were very demanding and challenging. I had never seen tutors challenge each other so fiercely, it required me to go to the library to check out who they were so as to figure out where they were coming from. We as students were expected to be no less critical in these crit’s. We were encouraged to visit exhibitions, art galleries and museums to discuss what we experienced. A number of our tutors were showing in these exhibitions.

You understood that discipline gave you the freedom to do what ever you wanted. I was on the B course where we had people working with objects, film, photography, performance and sound happenings. The culture was one where we were seen as artists and had to engage with all these expectations.

As a visiting artist at various universities and workshops, including Syracuse University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, what insights did you gain from teaching and collaborating with students and other artists?

These had very different cultures to St. Martins. They were more controlled and directed by one individual, whereas St. Martins was open and had many more voices contributing to the subject. This was a culture of artists, whereas most other institutions were teacher lead. This gave an intellectual freedom to the culture at St. Martins, in my experience a very unique situation.

Many of your exhibitions have been held internationally, including the Serpentine Gallery and Flowers East. How do these various cultural and geographical settings influence the reception of your abstract steel sculptures?

You have to take on board the nature of the setting’s you exhibit in, curating to the demands of the space and context. Exhibitions are a fundamental learning process, seeing your work in these contexts, out of the studio brings a very different reality to your work. The feedback is also important, but your own experience will be critical as to how you move forward.

In addition to individual awards, your work has been featured in prominent collections like Tate and the Gulbenkian Foundation. How does it feel to have your art represented in such significant institutions, and how does this impact your future projects?

It is important that your work is represented in significant collections, it gives you confidence and also helps with generating income and further exhibitions.

As someone who has been part of the art world for several decades, what advice would you offer to young sculptors who are just beginning their artistic journey, particularly those interested in working with industrial materials like steel?

Follow and support your instinct.