On the Edge of Figuration – Anne Moses’ Journey Through Detail and Ambiguity

The artist shares her process of capturing universal human expressions through close-up studies of texture and form

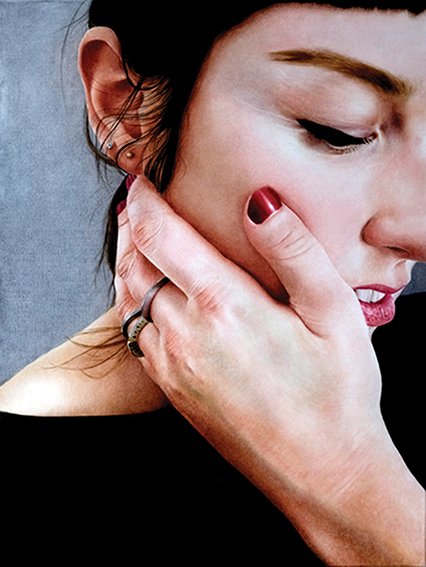

Anne Moses explores the human face and form through detailed portraits, blending traditional techniques with modern digital manipulation to create ambiguous, larger-than-life representations that challenge viewers’ perceptions of realism.

Capturing the essence of the human form with a unique blend of contemporary techniques and Old Master traditions, Anne Moses stands as one of today’s most evocative figurative painters. Her work explores the delicate balance between realism and abstraction, inviting viewers to examine minute details—skin textures, subtle expressions, and fleeting moments—while challenging their perceptions of human representation. From the softness of an eyelash to the delicate folds of fabric, Moses’ paintings push the boundaries of figuration, creating “images on the edge” that linger between observation and interpretation.

In this insightful interview, we dive into the creative processes that guide Moses’ practice. She shares her fascination with the human face, her evolution as an artist, and how teaching disadvantaged adults shaped her understanding of art’s transformative potential. The author skillfully guides the conversation, uncovering layers of emotion, technique, and introspection, which highlight both Moses’ profound artistic philosophy and her technical mastery.

Your work has remained focused on the human face and form, with close-up, highly detailed observations of skin and texture. What first drew you to these themes, and how have they evolved over the course of your career?

I’ve always been drawn to the human face and form, I’m not sure why but I do believe there is an innate mimetic response in all of us to re-present our own image in some way.

I remain fascinated by texture and details, I now accredit this to always being short sighted and looking closely at things. This has evolved over the years into enlarging these images so they become larger than life size, forcing the viewer to ‘look’. They almost become quite abstract, I call these images ‘images on the edge of figuration’.

You’ve described your work as capturing “fleeting moments” and translating them into paintings. How do you select and interpret these moments, and what role does introspection play in this process?

There are 2 strands to my working method. I often select certain people who catch my eye to pose for me in the studio. I’ll take a whole series of photographs, some set up and some quite random. These people greatly vary, any age, sex or type but I just see some quality which I relate to in some way either visually or emotionally.

I also constantly carry a camera around with me taking ‘chance’ photographs of people – maybe part of a face, a piece of fabric, a gesture, an expression…

Following the gathering of initial source material I spend a lot of time digitally manipulating these images ie; close cropping, enhancing/modifying colour, playing with composition etc. This is a massive creative part of the process for me which allows me to capture that fleeting moment which just speaks to me in some way – universal part-portraits we can all relate to…

You employ a combination of modern digital manipulation and traditional Old Master techniques, such as oil glazes. How do these approaches complement each other, and how do they impact the final result of your paintings?

As stated above, the digital manipulation of the original source material is probably the most creative part of my process where many chance elements can happen alongside controlling the overall image.

I discovered the oil glazing technique by chance which I have used for the last 8 years or so. It was a massive breakthrough for me in terms of technique. Whilst wiping off a painting which I just wasn’t happy with, I loved the effect of the white ground showing through, it gave the painting ‘life’. My husband (also an artist) and I worked on how to reproduce the watercolour technique of not using white paint but working in transparent colour whilst wiping off for the highlights. Oil glazing is a well known old master technique used to enhance and enrich colour, however, I’ve taken this technique and used it in its own without any opaque paint to achieve a glowing, luminous quality in my work.

We developed our own slow drying glaze from a very old ‘recipe, in a wonderful old book called Formulas For Artists!

Before transitioning to full-time art practice in 2015, you lectured in Art & Design, helping disadvantaged adults gain access to higher education. How did this teaching experience influence your own art practice or the way you approach your work?

I loved teaching adults. The course written, managed and delivered by my husband Steve and myself was a wonderful opportunity for 19+ adults who, for whatever reason, hadn’t had the opportunity or qualifications to progress their education. It was designed to develop and extend their fundamental skills in art and design alongside their own creative potential. The success of this course stimulated and excited me, to see people, often with very low esteem and confidence, grow as people and as artists is very rewarding, it was a privilege to be part of their journey. All progressed to Higher Education over 20 years.

Teaching on such a course and constantly reviewing our methods definitely kept me thinking about my own work, it often fed directly back into it.

Your paintings often explore ambiguity, particularly through montaged images and fragments of life seen up close. How do you use ambiguity to engage viewers, and what emotions or responses do you hope to evoke through this approach?

I often take the initial image to the ‘edge of figuration’ giving it an almost abstract quality. The emphasis I sometimes place on certain aspects of an image can just move the viewer away from seeing it as totally realistic or photorealistic, a subtle shift of perception.

It’s all about looking closer for me, seeing the beauty or fascination in the small things. Ive noticed that people often comment on an eyelash or a hair as if they’ve never really seen one before which of course isn’t the case, its just a surprise sometimes to see these small details larger than life size.

You’ve exhibited both nationally and internationally, with your work held in several private collections. How does exhibiting in different cultural contexts shape your understanding of how your art is received, and do you notice varying reactions to your work based on location?

People have often commented on the luminosity in my paintings when they actually receive them, I noticed this particularly when I exhibited in Paris. I haven’t really noticed massive difference in reaction to my work, I have received very positive feedback from countries as varied as Australia to the Philippines!

You’ve mentioned that there is an innate human response to the “mimetic” — the re-presentation of our own image. How do you see your role as an artist in controlling or transforming this representation, and how does it shape the emotional depth of your portraits?

I never used to think about this, I simply enjoyed and have always been drawn to the human face and body but following the reactions I get to my work I began to realise that people really do naturally respond to re-presented images of themselves and people around them, I suppose that’s why digital photography and now selfies are such a phenomenon and will never disappear. I have a response to certain subjects which is an emotional response, maybe just to a particular gaze or expression of sadness or introspection that someone has or maybe just a sensual response to the light on a face or a piece of fabric.

Although I have done portrait commissions I don’t think of my work as being individual portraiture, more a universal take on the representation of our own image – in a small way.