Cecile Chong – The Art of Layering Identity

Cecile Chong explores the intersection of culture, heritage, and social justice in her transformative multimedia installations

Cecile Chong explores her multicultural background, the impact of public installations, and the connection between art, identity, and social justice.

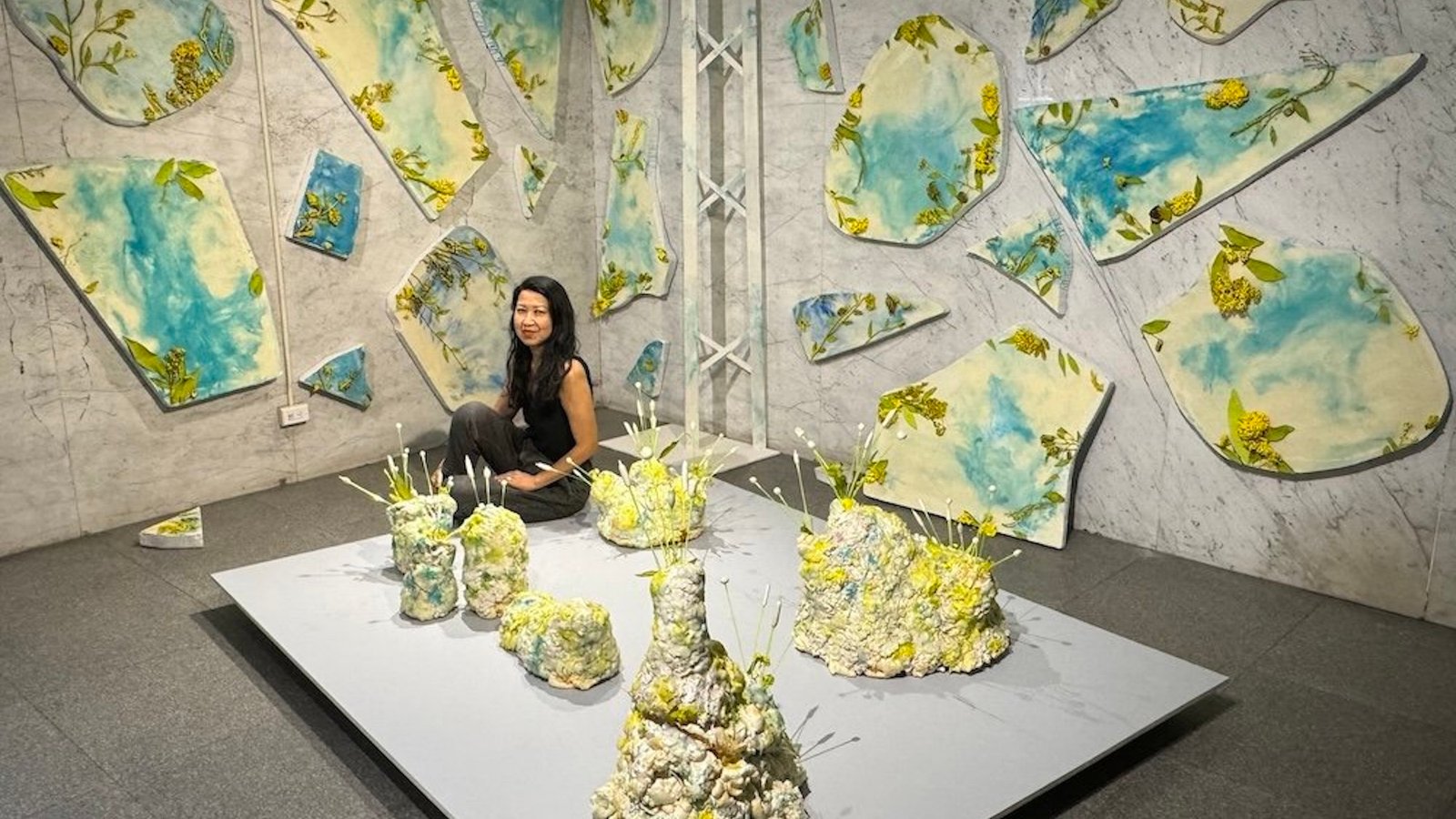

Cecile Chong’s multifaceted artistry emerges as a vibrant tapestry woven from her rich cultural heritage and profound understanding of identity. Born in Ecuador to Chinese parents and raised across the diverse landscapes of Quito and Macau, Chong has settled in New York City, where her experiences continue to inform her innovative approach to multimedia art. She masterfully intertwines painting, sculpture, installation, and public art, creating works that resonate with the complexities of layered identities and histories. Her installations, such as the poignant EL DORADO – The New Forty Niners, reflect not only her artistic vision but also her commitment to engaging with the cultural nuances of urban spaces. Through her art, she fosters a dialogue about belonging, migration, and social justice, urging audiences to recognize the interconnectedness of humanity.

Chong’s artistic practice is characterized by a remarkable ability to layer materials—ranging from volcanic ash and natural seeds to found objects—each symbolizing distinct cultural narratives. Her installations invite viewers to explore their own connections to the themes of heritage and belonging, making her work both personal and universally relevant. Her exhibitions have graced esteemed venues and institutions, solidifying her place in the contemporary art world. As a member of various artist communities and organizations, Chong’s contributions extend beyond her own practice, fostering collaboration and dialogue among diverse artists. In this interview, she shares insights into her creative process, the challenges of balancing personal and universal themes, and her deep-seated commitment to social justice through art.

Cecile Chong’s innovative artistry transcends cultural boundaries, weaving together personal narratives that resonate deeply with universal themes of identity and belonging.

Your work explores the layering of materials, identities, and histories. Can you elaborate on how your multicultural background influences these themes in your art?

Being born in Ecuador to Chinese parents and growing up between Quito and Macau, and finally settling in the US, I’ve navigated different cultural landscapes that constantly influence my perspective. The act of layering in my work is a direct reflection of the layering of these multiple identities. It represents the complex interplay of traditions, languages, and experiences that come from moving across cultures. My materials, whether natural elements like volcanic ash from Ecuador or found objects such as beads (representing cross-cultural commonalities) and circuit board materials (representing shared technology), act as symbols of these layered histories. By layering, I set up a juxtaposition and dialogue between these entitles as the figures in my paintings are often in dialogue, so are the materials and the landscape they inhabit.

In your public installations like EL DORADO – The New Forty Niners, how do you engage with the diverse cultural contexts of the urban spaces where your work is displayed?

In EL DORADO – The New Forty Niners, I made sure each installation resonated with the specific cultural context of New York City’s five boroughs. The sculptures of guaguas (Quechua for baby or child), a symbol of our common humanity, allowed me to create site-specific works that paid tribute to the 49% of NYC households that speak a language other than English.

At Snug Harbor on Staten Island, the sculptures were painted in white and blue to refer to the area’s maritime history, while they were installed six feet apart as a nod to social distancing during the pandemic. At the Lewis Latimer House, the faces of the sculptures glowed in the dark to honor Latimer’s invention in lighting technology. At Wave Hill, a beautiful public garden, the sculptures took on a floral form. At Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza, a block away from the United Nations, they were installed on 17 color planks, representing the 17 UN sustainability goals https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/. Each installation was tailored to connect with the unique historical context and character of its site.

Can you tell us about any specific project that challenged you in terms of balancing your personal heritage with broader, universal themes?

I had the impulse to bead on mundane objects and eventually settled on kitchen strainers. The challenge was trying to figure out what that meant.

In my Strainger Series, I focus on ideas of identity and perception. The word “Strainger” plays on “stranger” and “strainer,” symbolizing the filtering of experiences. Using kitchen strainers as masks, I explore the act of separation, liquid from solid, interior from exterior, insider from outsider, the exotic from the mundane. The beaded image of a guagua on each strainer reflects the nurturing aspect of culture. I repurpose necklaces and natural materials from Ecuador such as tagua, huayruro, pambil, and natural seeds from the Amazon, blending personal heritage with broader ideas of belonging and otherness. This series connects my narrative with global discussions on identity. In most cases, as in this one, I am inspired to make something. Trying to figure out what it means is often the challenge.

Given your extensive participation in artist residencies, how do these experiences shape or shift your creative process over time?

I look at each residency with as a new and interesting problem to be solved. I tend to immerse myself in the immediate landscape, often sourcing materials directly from the grounds or the compose heap to create site-specific wall or room installations. Whether it’s natural elements like leaves or branches or found objects connected to the site, these materials become central to my work. They allow me to create installations that resonate with both the environment and the broader themes of commonality in the human condition, migration, and environmental concerns, making each project deeply rooted in its specific context.

Do you think a lot about social justice when creating your work?

The foundation of equal justice lies in recognizing our shared humanity and seeing ourselves reflected in one another. Justice and equality require acknowledging that our differences do not make us separate but rather enrich the collective experience. By identifying commonalities—whether cultural, social, or environmental—we can build a stronger sense of empathy and interconnectedness.

In my work, I explore this idea through the themes of migration and environment. In EL DORADO, my work celebrates the contributions of immigrant communities, urging viewers to see themselves in these diverse stories. Similarly, in pieces like _other Nature, I challenge viewers to perceive nature as an extension of themselves, and ourselves as an extension of nature, emphasizing that justice is only achievable when we embrace our equality with each other and the world around us. Recognizing our shared essence is essential to building a just and inclusive society.