Exploring Time and Memory in Photography

Roi Kuper reflects on his artistic journey and the philosophical themes that shape his evocative work

Roi Kuper discusses his exploration of time, memory, and mortality in photography, sharing insights into his creative process and the impact of his work on viewers.

Roi Kuper stands as a profound voice in contemporary photography, captivating audiences with his exploration of the intricate relationships between time, memory, and mortality. His work, steeped in philosophical inquiry and artistic mastery, invites viewers to contemplate the complexities of existence through hauntingly lyrical imagery. With a career spanning several decades, Kuper’s exhibitions at renowned venues like the Tate Modern and the Israel Museum reflect his significant contributions to the photographic medium, showcasing a distinctive ability to evoke deep emotional resonance and critical reflection.

Through his acclaimed bodies of work, including “Vanishing Zones” and “Necropolis,” Kuper masterfully captures the ephemeral nature of human experience, often invoking themes of decay and nostalgia. His innovative techniques and profound narratives challenge viewers to engage with the images on multiple levels, prompting introspection and dialogue about the passage of time and the remnants of memory. As a recipient of prestigious awards, Kuper not only enriches the art world with his creative vision but also cultivates the next generation of artists through his esteemed academic role at Shenkar College. In this interview, we delve into the philosophical underpinnings of his work and the artistic processes that continue to shape his remarkable journey.

Roi Kuper’s photography uniquely intertwines philosophy and artistry, evoking deep emotional responses while challenging viewers to reflect on existence and memory.

Your work often deals with themes of time, memory, and death. What draws you to explore these philosophical topics through photography, and how do they influence your creative process?

Death is everywhere, in every image, if you look at it with an inquisitive and critical eye. My works don’t deal with death directly, but I am always aware it is lurking.

Time and memory are indeed present in my works because the viewer’s gaze is immersed in memory and it is he who drives the individual deciphering action and changes through time. Because memory is not fixed, it is flexible and changing.

It is the nature of photography, to resist time, to resist the fixation of reality, which also requires interpretation and necessarily presents many possibilities depending on the interpretation.

In the Atlantis series, 23 images are placed that are similar at first glance but not identical to a continuous, in-depth gaze. I try to eliminate the initial view which is usually easy to understand and flat in its interpretation. An extended viewing time allows the viewer to delve deeper within himself and create a more interesting, more enjoyable translation/interpretation.

But yes, you have to make an effort.

In your series “Vanishing Zones” (1991-1994), the images evoke a sense of disintegration and timelessness. Can you share more about the manipulation process involved in creating these existential black and white images?

The works on the Vanishing Zones series were photographed with small toy cameras, and printed in small size on photographic paper. Then the layer of the emulsion was separated from the paper, with the image becoming a negative.

Some were printed many times to the point of losing parts of the image and some were buried in the ground for long periods of months, taken out, washed and reprinted with all the marks of the damage caused by time.

At the end of the process, they were photographed on a large format photographic film and printed.

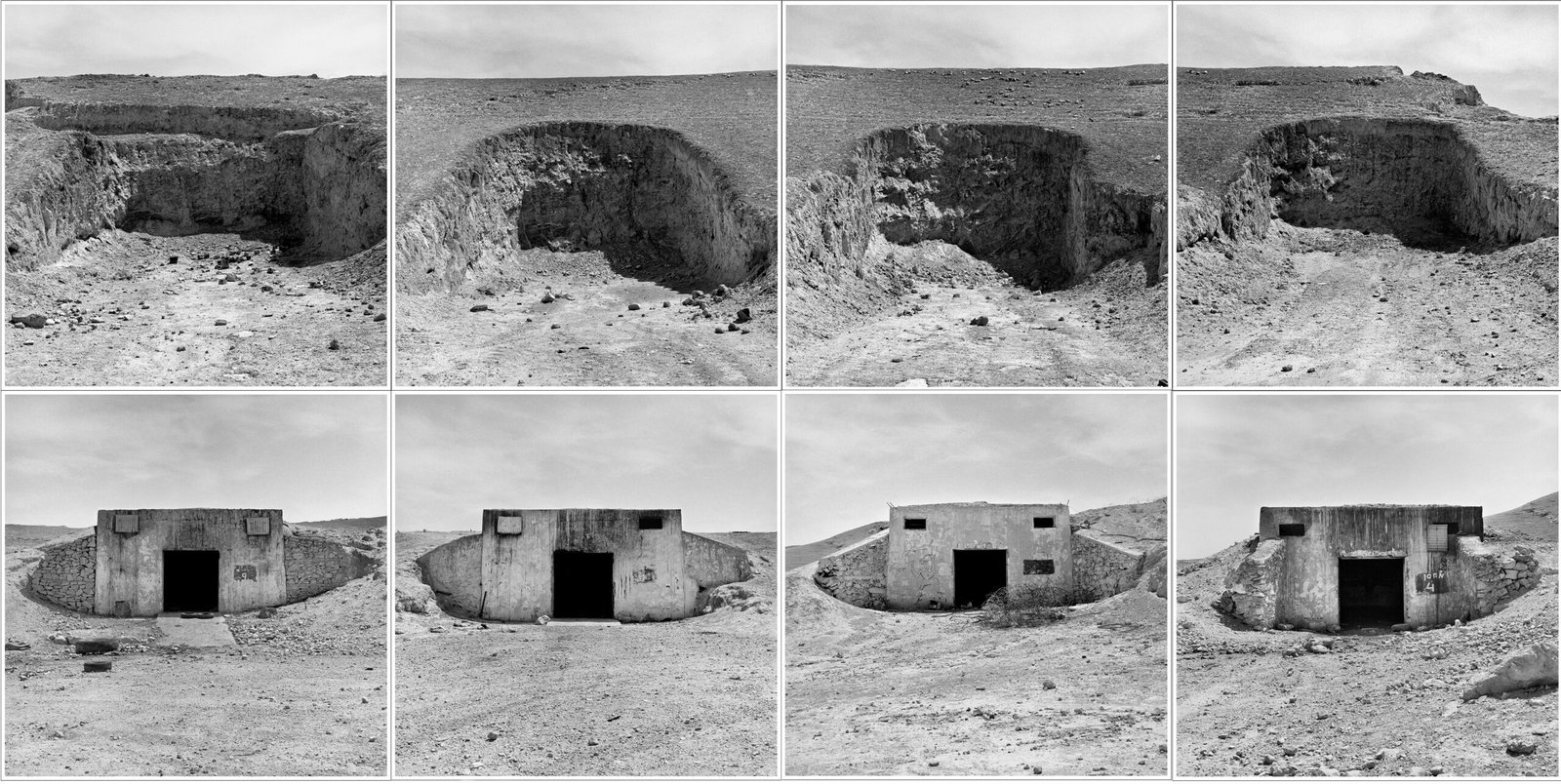

“Necropolis” (1996-2000) investigates deserted areas and military remains in the south of Israel. How did the combination of these landscapes and historical remnants shape the lyrical yet haunting tone of this body of work?

Abandoned military sites, abandoned military buildings, are images with a powerful visual charge, in the sense of the photographic gaze. In my view they are overly charged, to the point that this leads the gaze to a predictable and sweeping place.

That was what led the decision to shoot the Necropolis series is a thoughtful, lyrical manner, despite the directness of the camera. Some Necropolis photographs are inspired by the Bechers, a photograph of the thing itself while the background and the place remain secondary and unremarkable. In contrast, there are the works that look at an open, wide landscape that seems to ignore the military theme, but it is there and emphasized in the typological photography.

Two more series on the same subject: War Situations (2006), a work made of four photographs, examines the Reim camp built for the purpose of secession from the Gaza Strip with white tents in the distance, beyond a potato field with a row of sunflowers separating the field from the camp. The name of the series is taken from a poem by Maya Bejerano.

Gaza Dream (2015), a series that encompasses the Gaza Strip along the entire length of the Gaza-Israel border and extends to Gaza like a distant dream, a pastoral sight that confronts what is seen and what is known. While I was working on this series, in 2014, another round of war broke out.

Your exhibitions have spanned many renowned venues, including the Tate Modern and the Israel Museum. How do different audiences, both in Israel and abroad, respond to the themes and emotions conveyed in your work?

It is true that the Necropolis series is distinctly Israeli photography, a country full of military bases, contemporary and historical, some of which are abandoned and some of which are active. But the series operates in the gap between what you see in the works and what you know or think you know, usually from the press.

On one level, the Israeli viewer empathizes and identifies while the international audience abroad reads and tries to understand.

But I believe that most of the responses boil down to the insane absurdity of military investment, as in many places in the world throughout its bloody history.

You’ve won several prestigious awards throughout your career, such as the Ministry of Culture Prize for Arts and the Leon Constantiner Prize. How have these accolades impacted your approach to art and your development as an artist?

Awards make me happy for the appreciation given, they give strength to continue my wanderings as an artist who works alone.

I guess they spur me on to delve deeper into the topics I’m working on, the thoughts that lead me.

As an associate professor at Shenkar College and former head of the Multidisciplinary Art School, how has your academic career influenced your artistic practice, and what role does teaching play in your creative journey?

My academic career culminated in my professorship at Shenkar College, a multidisciplinary art school that I was one of the founders of, and that set as its vision to understand, accommodate, and accept the young students in their differences over time and put the students first

As the head of the multidisciplinary art school in Shenkar, I got to know the students from other angles within the academic system. This demanding role did take a toll on my artistic work (time demanding), but it was worth it.

The academic career affects the artistic activity as much as the artistic activity influences the academic career. As a lecturer and as an artist I did not separate them, I always believed in mutual fertilization, the artistic and philosophical questions that preoccupied me were present in my classes.