David J. Forsyth Explores Life, History, and the Art of Storytelling

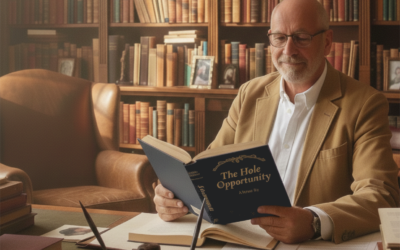

Photo: David J. Forsyth, author and historian, crafting timeless stories inspired by family legacy, personal experience, and a passion for history.

Genealogy and the Stories of Ordinary People

David J. Forsyth, Canadian author and historian, discusses his deep love of genealogy, the art of storytelling, and his creative journey from memoir to fiction and historical narratives.

D avid J. Forsyth‘s literary journey is nothing short of extraordinary. His works, deeply inspired by a rich tapestry of personal experiences and a lifelong passion for genealogy, transport readers through time and immerse them in the lives of ordinary people who lived extraordinary stories. From his heartfelt memoir Dafydd to his intricately researched Alice and The Machine Gunner, Forsyth has a remarkable talent for bringing history and personal narrative to life. As a Canadian author, his roots—tracing back to Irish, Scottish, and English heritage—have profoundly influenced his storytelling, providing a foundation of cultural richness and historical depth.

In this issue of Mosaic Digest, we have the privilege of delving into the mind of David J. Forsyth, a writer who masterfully captures the essence of family history, human resilience, and the beauty of life’s fleeting yet defining moments. His ability to transform everyday occurrences into compelling narratives speaks to his unwavering dedication to preserving the stories that might otherwise fade with time. His tales, whether nonfiction or fiction, are a testament to the importance of memory and the unbreakable bond between one’s past and future. We at Mosaic Digest are honored to share his insights, inspirations, and reflections in this exclusive interview. Whether you’re a seasoned genealogist, an aspiring writer, or simply a lover of meaningful literature, Forsyth’s words promise to inspire and linger long after you’ve turned the last page.

What inspired you to write your first manuscript and how did your granddaughter’s question spark the idea?

When my granddaughter asked what things were like when I was a boy, I began telling my grandchildren bedtime stories about growing up in the 1950s. Eventually, one of them complained, “You already told us that story, Papa.” Within a few days, I began organising and documenting my memories, then self-published the resulting manuscript as a gift to them. As a life-long amateur genealogist, I recognise the importance of memoirs, which like wine, become more valuable with age. My ego enjoys the idea that a descendant might one day rediscover Dafydd.

How did your background in commercial art influence your writing style and approach to storytelling?

I’m not sure my early employment as a commercial artist impacted my writing, unless my tendency to visualise what I’m writing about is a result of thinking in terms of pictures. As a commercial artist, my effort to create the best possible image negatively impacted my daily output, whereas my time consuming search for the perfect phrase or word has little impact on my publisher, who patiently waited four years for Alice and The Machine Gunner,which demanded hundreds of hours of research.

Can you tell us more about your genealogical research and how it has impacted your writing?

I detested history in school yet found my grandmother’s recollections incredibly interesting; so much so that I pestered her for more details. History becomes real when it involves one’s own family, and the history of ordinary people has its own intrinsic value. Years before internet access, in my quest to know more about my ancestors, I poured over census returns and records of births, marriages and deaths. I was fortunate to have lived near a Church of Latter Day Saints library, which offered free access to many records. Though genealogy begins with stark facts, it ultimately leads to an intimate understanding of day to day life in unfamiliar places and times. My books, Dafydd, Too Cold for Mermaids and Alice and The Machine Gunner are accounts of real people, true stories that will one day become the history of ordinary people.

What was the most challenging part of researching and writing the story of the war-brides and soldiers of the twentieth century?

Perhaps because I’m afflicted with a touch of undiagnosed OCD, I chose to decipher and transcribe hundreds of pages of hard-to-read handwritten military records before deciding whether or not they were useful. I had to learn World War One military terminology and acronyms, and make sense of the complex organisation of military units. The effort was compounded by the fact that my protagonist’s husband also served in World War Two. In summary, I suppose my biggest challenge was compiling huge amounts of potentially useful information and keeping it organised and available.

Your memoir, Dafydd, offers a unique glimpse into rural Canadian life in the 1940s and 1950s, what do you hope readers take away from the book?

Dafydd, which incidentally includes many urban recollections, describes period values and language as well as old technologies such as ice boxes and out-houses (outdoor privies). I initially hoped the book would help preserve aspects of day to day life likely to be obscured by time. I believed those born more recently would find it interesting, but to my surprise, my most enthusiastic readers are those who shared my experiences. I overlooked the fact that people love to reminisce.

What can you tell us about your collection of short stories, “Shadows and Reflections”, and what inspired the themes and characters?

Shadows and Reflections, my first tentative incursion into the genre of fiction, taught me how much of an author’s life experience inadvertently creeps into their characters and plots. One can’t avoid weaving their own experiences, values and fears into their fiction. For example, The Tinners Arms was inspired by my realisation that I might some day find myself alone and grieving for my late wife. As I wrote and rewrote those 5,000 words, I came very close to living the experience, and periodically had to quit writing to wipe the tears from my eyes.

When I was a young man, recently trained in emergency first aid, I attended a four-year-old boy, who was seriously injured when struck by a car. It was a horrific experience which haunts me even now. In my short story, The Memory, I invented a character named Ernie, and relived a fictional version of the painful incident. Not all of my short stories were based on actual events, but the best ones were.

What advice would you give to fellow authors who are looking to draw upon their own life experiences and family histories as inspiration for their writing?

Obviously, a long life, chock full of adventure, provides an author with abundant raw material. Young authors and those who feel their lives have been uneventful are somewhat disadvantaged though extensive research can to some extent compensate for a lack of life experience. Regardless of one’s genre, seeking knowledge and adventure is, I believe, paramount. Keeping a daily journal is advisable, but perhaps the best advice for aspiring authors is Ray Bradbury’s suggestion to, “Write a short story every week [for a year]. It’s not possible to write 52 bad short stories in a row.”

If one delves deep enough into their ancestors’ lives, incredible stories are likely to emerge. For example, my short story, Three Shilling Passage, is a fictionalised account of an ancestor’s court-mandated exile to Australia in 1834. The plot, dates and names are real, but due to a lack of recorded detail, much of the story is what I call “speculative” fiction. Only after substantial research into period court proceedings, London’s Newgate Prison, the protagonist’s origins, the ship on which he sailed, and the conditions he likely faced throughout his seven-year sentence, did I feel competent to speculate about the unknown aspects of the man’s ordeal.

Finally, if you haven’t begun writing, take the first step; write a page or two. Don’t worry about whether it’s profound, interesting or well-worded. You can re-write it a hundred times if you wish, but not starting has likely thwarted more books than have ever been published.

What three books have most influenced you and your writing and how?

One of the first books that I remember reading was Robert M. Ballantyne’s 19th century novel, The Coral Island. It’s story about three boys castaway in the Pacific sparked my love of the tropics and inspired Diego’s Island, the book I’m currently writing.

Though I was always curious and eager to understand the world, the late Carl Sagan’s Cosmos helped me appreciate the value of well constructed communication. Sagan, an American astronomer and planetary scientist, was able to describe very complex ideas so clearly and concisely, that I found most of them easy to grasp. His book taught me to ensure that my choice of words and phrases accurately convey my intended message.

Finally, Farley Mowat’s Never Cry Wolf, aside from being incredibly entertaining, is an impressive example of story-telling. Sometimes, I have to remind myself that my narratives are nothing more than stories, and I as a story-teller, I have a solemn responsibility to my readers.